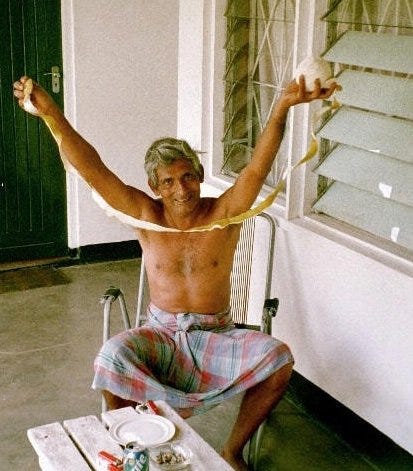

When you see this picture what do you notice?

To unfamiliar eyes, the observations may include: a strange looking brown man, with an oddly pleased grin, salt-and-pepper hair, seeming to be wearing a skirt, holding up a peel (??) and a fruit proudly. On the table before him: a plate, a cigarette lighter, an ashtray, a can of sprite.

This is my father. I called him Thathi - father in Sinhalese, one of the languages of my birth-country, Sri Lanka. This photograph was taken on the verandah of a house we visited in the Blue Mountains of Jamaica. Thathi is wearing a sarong, a simple but versatile garment: a bolt of cloth sewn into a kind of tube, which is knotted at the waist, providing a waist-to-ankle coverage at full length, shortened handily to waist-to-knee length by a second knot. Like a kilt, it is worn without underpants.

My father was the preparer of fruit for us when we were children:

sugar cane was peeled and cut into easily chewable portions for juvenile mouths, the hard joints set aside.

jackfruit was carefully cleaned, the sticky gum removed, the pegs carefully gathered so we could enjoy them without the mess.

mangos, peeled and cut, squishy bits removed.

grapefruit (like the one he is holding), peeled, the white pithy parts removed, and the pegs individually peeled, so all we had to do was stuff the edible parts into our delighted mouths, anticipating the burst of flavours as we bit down.

Thathi delighted in peeling a fruit in one long, unbroken stretch - a feat he accomplished often, and captured in this photo - hence the look of accomplishment on his face! Not that there was anything intrinsically wrong if the peel broke, but what a joy if that skin could be removed in one smooth stretch without a break.

The wholeness he sought for the grapefruit skin (or ortanique skin or orange skin) was like the wholeness he sought for the skin of his daughters. He did not did not ever want us to experience broken-ness due to the skins we were in. One of the reasons he moved our family from Sri Lanka to Jamaica (and not a “developed” country, a “first world” country, like England, USA, Canada or Australia) was because of his own experiences as a young adult, of broken-ness due to the skin he was in.

Immediately following marriage, my father moved to London, England, where he was eventually joined by my mother, and where they stayed until they were pregnant with my older sister. Most brown immigrants to the UK would have sought to have their children there, giving their offspring the “privilege” of British citizenship. But Thathi, having experienced the racial dis-privilege of being a brown man in the UK, wanted our identities to be rooted in our Sri Lankan heritage.

Ammi (my mother) and Thathi moved back to Sri Lanka and in 1970 my sister was born, followed in 1974 by me. Shortly thereafter, for a number of reasons including a civil war in Sri Lanka, Thathi sought to move his young family. He applied for work, intentionally, in countries where the colour of our skin would not be a disadvantage, and if possible, could even be an advantage for us. He looked at jobs in Africa and the Caribbean, where brown was privileged over black - at least back then.

This meant that, besides enjoying fruit carefully prepared by his hands in Jamaica, I enjoyed growing up in a country where the colour of my skin provided privilege. This skin - my father’s and my mother’s skin - was an advantage in the Jamaica of 1977 when we arrived. An era in which very few front-desk positions were occupied by darker skinned people. As the gap between emancipation and the present day grew, this privilege diminished, but a head start is a head start, anyway you look at it. My sister and I are beneficiaries of this carefully calculated head start.

I didn’t realize when I was growing up in Jamaica that my father’s wisdom and discernment in moving us to Jamaica provided me with a particular resilience - a capacity to be cut without breaking open - like Thathi’s treatment of the grapefruit in the picture.

Growing up, we learned, even memorized the history of colonization in Jamaica - a country where the Indigenous peoples, the Taino or Arawak, were completely wiped out. But that learning was mostly academic. I did not understand the implications of colonization in my own life quite so well. But, as we grow, we learn, we understand.

As a child, sometimes I found Thathi’s insistent wearing of the sarong to be embarrassing. It was his garment of choice at home. I had friends sometimes ask me,

“Why is your father wearing a skirt?”

Thathi also clung ferociously to the Sri Lankan practice of eating with his fingers, instead of a knife and fork. I remember one friend asking him,

“Mr Bandara, why aren’t you using a fork.”

Thathi replied with a grin, much like the one in the photo,

“I know where these fingers have been. Do you know where that fork has been?”

It was the rare occasion of social subjugation that found Thathi eating with a knife and fork, or for that matter, wearing closed-toes shoes (“We live in a tropical country, why should we wear uncomfortably hot shoes?”), or wearing a suit (similar logic, “we live in a tropical country, why should we wear an uncomfortably hot suit, because it the norm in England?”)

Thathi understood that even common “fashions” were influenced by colonial mores, and he stubbornly refused to give in. He favoured the 4-pocket “bush jacket”, or short sleeve Sri Lankan cotton batik shirts for dress-up events - both garments which he felt more suited the reality of the environment we were in.

As a child, I found his stubbornness embarrassing at times; the responses he would give to my friends, or to my mom, who much preferred if he would just fit in, would often just exacerbate my embarrassment. When he would come to pick us up from school, I always tried to be waiting for him, so he wouldn’t have cause to step out of the car in his rubber flip flops to come looking for us. Everyone else’s parents wore the appropriate (hot) close-toed shoes. I didn’t want them seeing his unusual footwear.

Thankfully, by the time I got through high school, I had a better understanding of his principles. I began to understand that he was claiming something by his unusual behaviour. He was claiming the wisdom of a heritage which understood the health and comfort benefits of clothing that suited the climate. He similarly claimed the wisdom of that heritage in numerous other ways. He was good at applying values based on thinking things through, rather than slavishly following superficial (and often harmful) mores.

When we were growing up in Jamaica, and throughout my adult years, before Thathi died (2006), he constantly and consistently reminded me of the privilege I enjoyed in so many things: education, skin-colour, physical and mental abilities, family, heritage. His reminder was always that privilege comes with responsibility.

Just because we have authority over a simple grapefruit, doesn’t mean we should handle it callously. Even a simple grapefruit skin deserves to be carefully peeled, and kept as whole as possible for as long as possible. He modeled for me: living out our responsibilities that come from our privilege can be a source of both joy and elucidation - do you know where that fork has been?

My heart is full of gratitude for the unbroken skin and the head starts we had in learning to discern what is truly valuable from Thathi's example as much as his words.

Lovely piece.